Speculative fiction loves its aliens. Whether they’re used for social commentary or to push the limits of human imaginations, they often deserve a stage all to themselves, in stories that focus primarily on aliens and alien cultures. Whether trying to comprehend an alien language (as in Ted Chiang’s Story of Your Life), or physically traveling into the unknown (like the characters in Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation), story conflict can be driven from an encounter with the “other”—and imagining a unique, plausible alien can be a thought exercise in itself. Consider John W. Campbell’s famous dictum on alien creation, which challenged authors to “write me a creature who thinks as well as a man, or better than a man, but not like a man.”

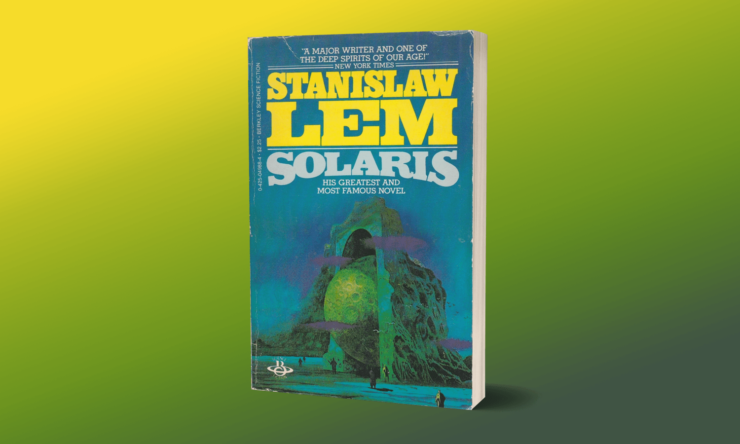

But can a human ever truly understand an alien? To explore the intricacies and complexities of this key question, science fiction needs novels like 1961’s Solaris—and Stanislaw Lem was the ideal author to write it. As a physician, his training in science lent an aura of authenticity that sells the reader on the novel’s white lab coat shop talk. But as a polymath who was also interested in philosophy, Lem is capable of taking the reader to a mental plane beyond the basic narrative. By the end, you’re left asking yourself how well humans can fully understand each other, or themselves, let alone a being from another world.

“The peculiarity of those phenomena seems to suggest that we observe a kind of rational activity, but the meaning of this seemingly rational activity of the Solarian Ocean is beyond the reach of human beings.” –Stanislaw Lem on Solaris

If we had a real-world Starfleet like the one featured in Star Trek and xenobiology was a course taught at the academy, Solaris could be required reading. There’s something almost subversive about a tale centered on highly trained researchers trying and failing to ‘figure out’ the alien. Perhaps young cadets would have much to learn from a story about failure and the reminder that such an undertaking might not be as simple as collecting and cataloguing specimens.

In many ways, Solaris is an anti-novel. Its main character, Kris Kelvin—at times stoic and collected, at times cold and aloof—is more an anti-hero than a typical protagonist. Like many science fiction novels from that era, a compelling concept sits at the heart of the story: confronting or making contact with an alien intelligence. But where other novels might play up the idea of a living, conscious ocean to entertaining effect, Lem deflates our expectations: Instead of concluding with a more conventional or satisfying ending, the reader is left with an anti-climax and anti-resolution.

Solaris, a quintessential novel of science fiction’s New Wave movement, contrasts strongly with the more colorful and optimistic Golden Age that preceded it. The movement challenged the old norms and embraced diversity—including a diversity of concepts. Unlike the often-naïve stories from a happier yesteryear (stories often cynically driven by a fast-paced, industrial pulp market designed to appeal to young males), the New Wave broke the genre by subverting the old conventions.

Unlike more traditional stories that placed scientists on a pedestal and extolled the achievements and possibilities of scientific exploration and experimentation, Lem’s novel is steeped in skepticism about science’s ability to unlock the mysteries of the universe. As the reader explores Solaris, following in the footsteps of previous expeditions to the unusual planet, tension is derived from active denial, frustration, and confusion rather than an antagonistic outside force.

Solaris escapes our attempts at defining, let alone understanding it. It’s a planet, an alien life form, a sentient being—and possibly a metaphor for the unknowable. The very process of assigning it a name or attempting to define it according to various classifications and attributes in many ways eclipses the effort of perceiving it in its truest form.

Before the first ‘solarists’ could understand what Solaris was, these fictional researchers already committed errors in their assumptions and “educated guesses,” however well-intentioned. Solaris exists as a puzzle that’s impossible to solve—a possibility that hadn’t remotely occurred to the surefooted humans determined to crack it. Its inherent unknowability feels uncomfortable to us. But the universe has yet to reveal its mysteries to us and doesn’t exist to serve our whims. Solaris simply exists. The absence of a clear message after so many years of forward-looking, human-centric stories and storytelling conventions feels a bit like a damp squib.

Despite Lem’s background in science, his depiction of the scientific process when applied to something as alien as Solaris is imbued with a sense of cynicism. Some science fiction authors, especially those associated with pulpier traditions, tend to use scientific terms almost as buzzwords to help evoke a rarified atmosphere of high-tech experimentation (i.e., “ion,” “nano,” and “quantum”). These are sometimes used in the appropriate context or are technically accurate, but they’re essentially a tool for SF authors trying to engage a potentially savvy audience. This use of jargon serves as both a rubber stamp and a form of currency in the genre, and Lem could play with along with the best of them. In Solaris, Kris Kelvin uses a neutrino microscope to study a physical sample. “Neutrinos” first entered the scientific vocabulary as a concept in the early 1930s and were first detected only in 1956, so the novel’s use of the term works both in terms of established hard science and as fashionable high-tech jargon. Neutrinos remains a popular subject both in science and science fiction as we’ve learned more about the particles and how they work, but in the world of the novel it simply made both logical and dramatic sense to use an advanced device with an exotic-sounding particle. It’s also, conveniently, a great MacGuffin.

That’s because in spite of their scientific prowess, the many different solarists, penning such works as the articles published in the Solarist Annual and Historia Solaris, seem at times like nothing more than butterfly enthusiasts or stamp collectors. At the limits of their knowledge, all they can do is document mysterious phenomena, building up a never-ending ocean of factoids that fail to solve or shed light upon Solaris’ perennial mysteries. What does mass, weight, or dimension tell us about the human condition? Or morality? Or ethics? Or ourselves, beyond the molecules of which we’re composed? The philosopher Hume said that you cannot derive a normative claim from an objective one—you cannot use deductive reasoning to say what ‘ought’ to be based on what ‘is.’ But there’s no reason to despair and fall off that cliff of nihilism. Hume’s Law reminds us that there are ways of reasoning beyond deductive: inductive, intuitive, modal.

Lem’s Solaris effectively turns his readers into solarists. Like the fictional researchers in his novel, we have been exposed to an experience that is difficult to talk or write about. At times it is eerie, unsettling, and frustrating. Like the solarists sifting through their volumes of lore, we are left, after putting down Lem’s book, wondering about our own Solaris. To what extent can any of us understand one another, or ourselves? Is true understanding even possible? What does understanding imply? What is intelligence? Does knowledge itself have inherent value or is it merely a means to an end? Will a pursuit of knowledge ever satisfy our need to understand, or is it just another ego-driven attempt at grasping the unattainable? Like our protagonist Kris, we can catalogue, dissect, and study the fictional world of Solaris in tiny discrete bits. Or, we can surrender to it, and in accepting the ineffable, enjoy what follows without trying to force it to make sense.

Jonathan E. Hernandez (@jhernandez13) is an author, visual artist, Brazilian Jiu Jitsu practitioner, and organizer with the Brooklyn Speculative Fiction Writers. After an honorable discharge from the military, he went back to school to study creative writing and pursue a career better suited to his muse. He lives in Astoria, New York with his partner and a cat named Jonesy.

Excellent piece, thanks! Solaris is perhaps the ultimate hard SF novel –even though the science here is epistemology more than anything else.

There is a case to be made that Lem’s point of view is less cynic than objective, as it refuses to go into the facilely optimistic, “science will always find a way” mentality. He wisely admits that knowledge is a process, and a process that can never stop unfolding, and never will. The failed relationship between Kelvin and the original Rheya/Harey mirrors this dynamic, since they remained a mystery to each other until the bitter end. I feel, however, that there is a grain of hope in the relationship between Kelvin and the second Rheya.

To this day, it remains one of my favorite novels ever, genre be damned, and it is a pity that both movie adaptations have served it rather poorly. Though I will always have a soft spot for Tarkovsky’s uneven but beautiful film, which I watched years before being able to read the book. (As for Soderbergh’s abomination, the least said, the better.)

Thank you! And thanks for commenting.

All that I can say is…pretty much? :D

Solaris really is hard to unpack and talk about. Maybe because it’s so rich in material. It’s one of those books that just kinda floored me and shut my mouth for a bit :3

I also think it’s one of those stories that just doesn’t translate well into film.

I agree with everything you said. It does make me shut up , too –which in my case is nothing short of miraculous… :-D

Fun fact I just discovered, rummaging through that friend of the lazy scholar, Wikipedia: There is a previous Russian TV adaptation of Solaris, made in 1968. It is supposedly the most faithful of the three.

However, considering the Russian idea of pace, and the Soviet aversion to philosophical ideas other than cheerfully and narrowly understood Marxism, plus what you rightly pointed out about the book being intrinsically hard to translate into other media, it is probably the grandmommy of all snoozefests.

I just want to say, you’re the man, Jonathan. This was great. And for anybody else who wants to read some more of his thoughts on spec-fic, go to http://www.bsfwriters.com/speculative-facts he wrote about 80% of theses posts.

This is perhaps an odd question, but: does the film Annihilation translate the themes and concerns of Solaris to the big screen in a way a direct adaptation of Lem’s work couldn’t achieve? (Much like The Lord of the Rings, I suspect Solaris can’t be adequately translated to film.)

@@@@@ 4: Thank you! MUCH appreciated.

@@@@@ 5: I don’t think that’s an odd question AT ALL. But I’ll let Jonathan have a go at it first.

What I think makes the question difficult is that there’s nothing obviously horrific about Solaris (except perhaps in a very abstract, philosophical sense) while Annihilation (book or movie) is expressly a work of Horror. Jack Vance wrote “Green Magic”, which touches on a lot of ideas dealt with by Lovecraft, but there’s nothing ‘Lovecraftian’ about the story or its characters.

Perhaps Solaris could be seen as being part of Weird fiction, without concerning itself with fear, even though much of the Weird is centered on that emotion.

@3 Ha! I think most people think about the Tarkovsky version and pretend the Soderbergh one just doesn’t exist :P

You may know this but he also directed a creepy/cool SF film called Stalker. It’s also an adaptation of a Russian novel called Roadside Picnic – another great alien absurdist story.

@@.-@ Thanks! :D

@5 Yeah I think Annihilation is another one of those hard to translate works. Solaris was creepy for me in an existential way and Annihilation was so visceral and gritty. The atmosphere that Vandermeer made with prose was sort of captured through visual storytelling, but all we can ever hope for is like an interpretation. Now I’m curious to see what Villeneuve will do with Dune.

@@@@@ 9: “Ha! I think most people think about the Tarkovsky version and pretend the Soderbergh one just doesn’t exist :P”

I know I do. :D

One of the too, too many things that irk me about Soderbergh’s “version” is that he specifically said in an interview that he was going to avoid any visual reference to Tarkovsky’s film. First thing you see? The absolutely identical orbital station.

“You may know this but he also directed a creepy/cool SF film called Stalker. It’s also an adaptation of a Russian novel called Roadside Picnic – another great alien absurdist story.”

One of my all-time favorite films. I like the novel just fine, but this one of those cases where the film is so much better –and very different as well.

If you haven’t read Hard to be a God, please do. I think it’s right up your alley. It’s not only a wonderful book, but also a book that manages to say some brave stuff about the Soviet Union. Do skip the movie, though.

As for Dune… The books haven’t aged well for me; maybe because I didn’t read them at the right age, I guess. It’s a pity that Jodorowsky rather “out there” project never got made, though there are many more echoes of it in David Lynch’s movie than anyone has ever cared to admit. I kinda, sorta, look forward to the new one, but not passionately so.

@@@@@ 5 & 8: Jonathan is probably right about Annihilation being also hard to translate to the screen. I haven’t read the book (beyond a paltry Kindle preview), but Alex Garland says that in so many words in the movie bonus materials –which are awesome, IMHO; just watching brave Gina Rodriguez being repeatedly (and rather roughly) slammed and dragged around by a gigantic stunt man is worth the price of admission.

I agree with your take on Annihilation. I think Lem and Vandermeer (and Tarkovsky, as Annihilation reminded me both of Solaris and of Stalker) are interested in the same themes and use some of the same motifs (the replication, for instance), but again, as you say, they do very different things with them. And Garland as well.

There is some horrific stuff in Solaris (the rather unusual visitors the other scientists have, for instance) but it stays under the terse surface.

Factoid does not mean what you think it means. Norman Mailer coined the term According to him it means something that looks like a fact and is presented as a fact but is not a fact. Think Fox News.

It does not mean a tiny fact or a disconnected fact or trivia.

I recently heard a long discussion on BBC radio of “Stalker”, which turns out to be, I think, part or most of “The Film Programme”.

Download from https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m00070ng

It also was the subject of their “Free Thinking” programme in 2016. Since I hadn’t consciously heard of “Stalker” before this year, this may be one that I missed listening to.

Play, if allowed, from https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b0775023

Having said that, Wikipedia has a fine in-depth article, so you may as well start there.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stalker_%281979_film%29

In Solaris if I remember right there’s not only the reflection about the scientific method and the possibility that we may not be able to comprehend or communicate with alien beings if we meet them, but also the mystery of human mind which the Solaris entity seems capable of entering to generate those “simulacra”.

Another novel by Lem with unfathomable aliens is “Eden”. I actually enjoyed it more than Solaris, which to my taste is a bit too much phylosophical. There’s more action and bafflement in Eden, the kind that only Lem is conjure up.

@@@@@ 13: Thanks for those links, Robert!

There is an excellent book about Stalker, Geoff Dyer’s Zona: A Book About a Film About a Journey to a Room. Dyer also headed a fantastic, all-star critic panel called Tarkovsky Interruptus that can be enjoyed here: https://thefilmstage.com/news/watch-a-75-minute-dissection-of-andrei-tarkovskys-stalker-with-walter-murch-geoff-dyer-more/.

Some enchanted evening, I want to watch the movie and the panel, the way those lucky people did at the New York Institute for the Humanities.

Anyone interested in this type of epistemological science fiction should check out another of Lem’s novels, His Master’s Voice. It centers on a message from the stars which spurs a Manhattan Project-level scientific bonanza to try to decipher the message, and a struggle between scientists and governments which are more interested in developing weapons than anything else.

As for @10 saying to stay away from the Hard To Be A God film adaptation – anyone with the stomach for arthouse cinema should ignore that message with extreme prejudice. Hard To Be A God is a film unlike any other, and probably Aleksei German’s masterpiece. If you can handle Tarkovsky, you should be able to handle this one.

@@@@@ 17: I can handle Tarkovsky and arthouse cinema just fine, but I could not stomach the Hard To Be A God movie. Partly because I love the book, and partly because it makes zero sense to me. You’re entitled to your opinion, of course.

PSE! Let us include FIRST CONTACT by Murray Leinster!

Keep reading!

Take care,

Phil

I’ve just read five other of Lem’s. Fiasco is excellent. Goodwill–another. The man was bubbling with ideas. Something woefully missing in the current genre. It’s all becoming too homogenized. Or turning into sociology 101. Science fiction is based on the premiss of what -science- means. It comes from the word: scientia. Something not even present in the current state this genre is in. Lem was one of those who did justice to this realm of exploring the alienesque. Now all we get is two dimensional pop up heroes and the odd heroine. Evil is always evil. Comic characters to the rescue is not science fiction. Stanislaw Lem should be required reading.

Fiasco is the one I would recommend. So focused on what this review takes from Solaris.

I actually like the Soderburgh Solaris. It’s not about humans trying to understand an alien planet, but I don’t think Solaris the book is, either. They’re about the people. Where Fiasco really is about scientists trying and failing to understand aliens, Solaris is mostly about an alien trying to understand people. Possibly even succeeding, in its own way.